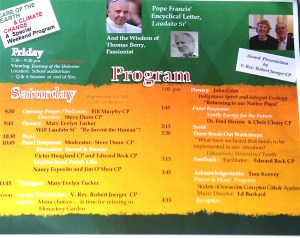

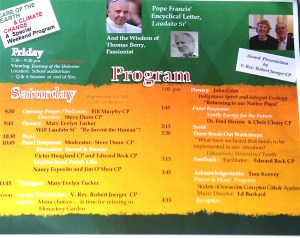

This weekend we had a program at our monastery in Jamaica, New York, entitled Pope Francis’ Encyclical Laudato Si and the Wisdom of Thomas Berry, Passionist. The main presenters were Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, senior lecturers and research scholars at Yale University.

The program began Friday evening with the award-winning film “Journey of the Universe” produced by Tucker and Grim along with Brian Swimme, which brilliantly portrays the story of our universe as science today explains it. On Saturday Mary Evelyn and John lectured on the pope’s encyclical, the influence of Thomas Berry and the contribution of native peoples to the critical question of the environment. I was among the commentators responding to their presentations:

I was one of Fr. Thomas Berry’s first students. It was at Holy Cross Preparatory Seminary in Dunkirk, NY in 1950. It’s usually not noted in biographical material about him, but Tom taught history to seminarians that year and I was in his class.

I remember the first day he came into class with a stack of booklets in his hands. “We have to know what’s going on today in the world,” he said, “and so we’re going to study The Communist Manifesto.”

Now remember, this was 1950. Senator Joe McCarthy had begun a witch-hunt to root out Communist sympathizers and I think The Communist Manifesto was on the church’s list of forbidden books. We studied it.

Yet, Tom never mentioned Joe Mc Carthy or the threats of a Communist takeover in Europe or what was happening then in China. No, he was interested in where the Communist Manifesto came from. Beyond Karl Marx and Lenin, he traced it back to the Jewish prophets and their demands for justice for the poor and human rights. The long view of history was what interested him.

After the Communist Manifesto, we studied St. Augustine’s City of God. Two loves are building two cities, Augustine said. Again, Tom didn’t dwell much on the historical events used by Augustine to illustrate his theory of history. It was the overall dynamic of the two loves in conflict over time that interested him.

From Augustine, we studied Christopher Dawson and his book The Making of Europe. Dawson, one of the 20th century’s “meta-historians,” wasn’t interested only in Europe; he was interested in the whole panorama of civilizations that came before it. That was Tom’s interest too.

As far as I remember, Tom didn’t speak of the universe and its evolution, his focus in later years, yet you could see him heading that way. He had a mind for the long view of things.

Pope Francis in Laudato Si also has a mind for the long view of things, it seems. The pope doesn’t quote from The Communist Manifesto, but he insists, more strongly than the manifesto, on the rights of the poor, to which he joins a strong insistence on the rights of the earth.

Can we also hear echoes of Augustine’s City of God in Laudato Si? I think so. The pope speaks of two loves in conflict. There’s the love that builds the city of man. How describe it today? How about blind consumerism; we love things too much. We love our vision of material progress too much. We love our technology too much. We love our control over the earth too much. We love ourselves too much. The result is “global indifference” to an environment falling apart. (Laudato Si, 9,14)

Opposing that love is a love the pope sees in Francis of Assisi, “who was particularly concerned for God’s creation, for the poor and the outcast…he would call all creatures, no matter how small, by the name of ‘brother’ or ‘sister’… If we approach nature and the environment without this openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs.” (LS, 13)

Berry, like the pope in Laudato Si, accepted science’s view of our environment, yet also like the pope he distanced himself from a major trait of the era of the Enlightenment which unfortunately causes us in the western world “to see ourselves as lords and masters of our environment, entitled to plunder her at will.” (LS, 2)

Science teaches us a lot about our environment and its perilous condition today, but knowledge is one thing and love is another. Two loves are at work. Love doesn’t always follow what we know, especially if our hearts are fixed on something else. Love is hard to change.

I heard the preachers and teachers and ordinary folk in the workshops that followed our workshop presentations bemoan the poor reception the pope’s encyclical has received so far. Why isn’t the environment a critical issue in our parishes, in the media and in the political world? Why aren’t we undergoing what the pope calls “an ecological conversion?”

There are many reasons, I suppose, but one thing seems sure. It’s not going to happen overnight through some quick fix. We need to get ready for the long haul. And what does that mean? We need wise teachers and leaders to guide us, like Thomas Berry and Pope Francis.

“The present time is not a time for desperation, but for hopeful activity.” Thomas Berry, CP

Victor Hoagland.CP