Callistus, the saint in our calendar today, was a slave who became pope in 217 AD. Slaves not only did lowly demeaning work in the Roman Empire, they were bank managers and school teachers and fulfilled other professional duties as well. Tradition says Callistus was a Christian slave who was a financial manager for one of Rome’s royal families. He was accused of mismanagement but then found innocent.

When Zephyrinus became bishop of Rome, he called on Callistus to serve as deacon in charge of a large Christian cemetery along the Via Appia, which today bears his name. Not only did Callistus bury the dead, he also cared for and supported the families they left behind.

Zephyrinus died in 217 A.D and Callistus succeeded him as pope by popular choice. Roman Christians saw him, not a slave, but a man of faith who could guide and lead them. The church grew under his leadership.

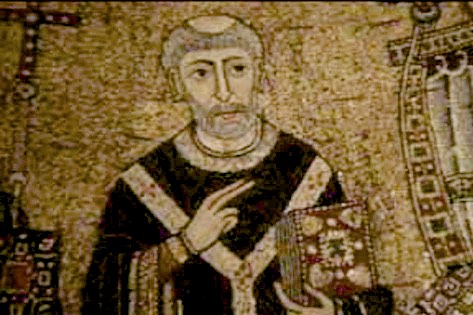

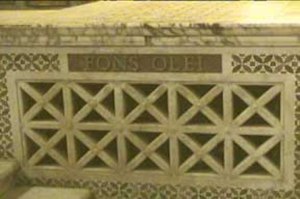

Tradition says Callistus built a place of prayer where healing oil welled up, at or near a hospice for old or sick soldiers in Trastevere. Today the beautiful Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere stands on the spot. Inscriptions from the cemetery of Callistus are embedded in its structure.The place where the healing oil was found is marked in the church and Callistus’ remains are buried under its main altar. He’s pictured in the great mosaic in the church’s apse. (above)

As pope, Callistus advanced certain causes. He favored free women being able to marry slaves. He favored ordination for men who had been married two or three times. He also maintained that the church could forgive all sins, even the sin of denying one’s faith.

Some opposed Callistus because his views clashed with their own rigorous views, but Callistus shared St. Paul’s conviction: There is “neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free person, neither male nor female.” (Galatians 3,28) Mercy is God’s gift to be experienced by all..

Callistus’ remains were found by archeologists in 1960. He is counted as a Christian martyr, but the circumstances of his death remain uncertain. The historian Eamon Duffy says he was murdered by a mob angered by Christian expansion in the already crowded district of Trastevere. (Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes, p 14) As Christians grew in number the church became a substantial property owner, caring for 1,500 widows and other in need by 251 AD.

On August 2, 258, Pope Sixtus II and four deacons were martyred while celebrating the Eucharist in the catacombs of Callistus in Rome. Four days later, Lawrence the deacon was executed. Rome’s emperors, like Decius and Valerian, annoyed by Christian expansion and seeking their assets, began a series of persecutions that led to the church’s further growth.