Today is the feastday of St. Gabriel Possenti, the young Italian Passionist who died in 1862 and was canonized in 1920. I’m interested in his connection with Fr. Theodore Foley (1913-1974), an American Passionist whose cause for canonization was recently introduced in Rome. As a young boy of 14, Theodore read about St. Gabriel and decided to become a Passionist; other young men joined the community in the early 1920s and 30s also influenced by the young Italian saint.

Today is the feastday of St. Gabriel Possenti, the young Italian Passionist who died in 1862 and was canonized in 1920. I’m interested in his connection with Fr. Theodore Foley (1913-1974), an American Passionist whose cause for canonization was recently introduced in Rome. As a young boy of 14, Theodore read about St. Gabriel and decided to become a Passionist; other young men joined the community in the early 1920s and 30s also influenced by the young Italian saint.

What was St. Gabriel’s appeal ?

The cause for beatification of Father Theodore Foley, C.P. (1913-1974) opened officially on May 9, 2008 in Rome, just two years after the North American Passionist Province of St. Paul of the Cross and affiliate members met in a provincial chapter, which endorsed a proposal requesting that Father Theodore, a member of St. Paul of the Cross province and former superior general of the community, be considered as a candidate for canonization. Appreciation for him has grown steadily over time, for Father Theodore exemplifies the quiet, steady loyal holiness needed today– rooted firmly in the past and reaching with Christian hope to the future. In his preface to Saint Gabriel, Passionist, a popular biography by Fr. Camillus, CP published in 1926, the powerful archbishop of Boston ,William Cardinal O’Connell, denounced the “flood of putrid literature which, for the past ten years of more, has deluged the bookshelves and libraries of our great cities, fueling disappointment and emptiness in a false romanticism.” He urged young Catholics to reject this falseness and live in the real world, like St. Gabriel:

“To live a normal life dedicated to God’s glory, that is the lesson we need most in these days of spectacular posing and movie heroes. And that normal life, lived only for God, quite simply, quite undramatically, but very seriously, each little task done with a happy supernaturalism,-that such a life means sainthood, surely St. Gabriel teaches us; and it is a lesson well worth learning by all of us.”

Young Theodore Foley took Gabriel’s path. He followed the saint into the undramatic life of the Passionists.

Gabriel Possenti’s decision to enter the Passionists has always been something of a mystery, even to his biographers. Did he choose religious life because he got tired of the fast track of his day? And why didn’t he enter a religious community better known to him, like the Jesuits, who could use his considerable talents as a teacher or a scholar? Why the Passionists?

Gabriel–and Theodore Foley after him– was attracted to the Passionists because of the mystery of the Passion of Christ. It was at the heart of God’s call.

The Passionists were founded in Italy a little more than a century before Gabriel’s death by St. Paul of the Cross, who was convinced that the world was “falling into a forgetfulness of the Passion of Jesus” and needed to be reminded of that mystery again. Paul chose the Tuscan Maremma, then the poorest part of Italy, as the place to preach this mystery, and there he established his first religious houses for those who followed him. He chose the Tuscan Maremma, not to turn his back on the world of his day, but because he found the mystery of the Passion more easily forgotten there.

When Gabriel became a Passionist, the community like others of the time, was recovering from the suppression of religious communities by Napoleon at the beginning of the century. In one sense, it had come back from the dead . The congregation was now alive with new missionary enthusiasm. Not only were its preachers in demand in Italy, but it had begun new ventures in England (1842) and America (1852).

Paul of the Cross, the founder, was beatified in 1853. Ten years earlier, the cause of St. Vincent Strambi, a Passionist bishop, was introduced. Dominic Barbari, the founder of the congregation in England, would receive John Henry Newman into the church in 1865; the English nobleman, Ignatius Spencer, who became a Passionist in 1847, began a campaign through Europe in the cause of ecumenism. New communities of Passionist women were being formed.

Respected for their zeal and austerity, the Passionists were a growing Catholic community, and their growth in the western world continued up to the years when Theodore Foley became their superior general and then saw its sharp decline.

Success was not what drew Gabriel–and Theodore Foley after him–to the Passionists. Their charism–the mystery of the Passion of Christ– was at the heart of God’s call.

As a boy growing up, Gabriel Possenti understood this mystery, even as he danced away the evening with his school friends. Twice he fell seriously ill and, aware that he might die, promised in prayer to serve God as a religious and take life more seriously. Both times he got better and forgot his promises. Then, in the spring of 1856, the city of Spoleto where he lived at the time was hit by an epidemic of cholera, which took many lives in the city. Few families escaped the scourge. Gabriel’s oldest sister died in the plague.

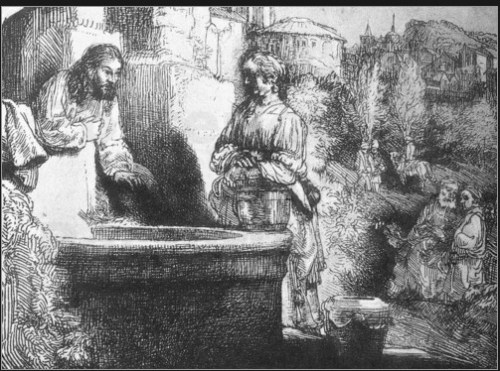

Overwhelmed by the tragedy, the people of Spoleto gathered for a solemn procession through the city streets carrying the ancient image of Mary, the Mother of Jesus, who stood by the Cross. They prayed that she intercede for them and stop the plague, and they also prayed that she stand by them as they bore the heavy suffering.

It was a transforming experience for Gabriel. Mysteriously, the young man felt drawn into the presence of the Sorrowing Woman whose image was carried in procession. Passing the familiar mansions where he partied many nights and the theater and opera that entertained him so often, he realized they had no wisdom to offer now. He took his place at Mary’s side. At her urging, he resolved to enter the Passionists.

Can we speculate, then, how the life of the Italian St. Gabriel drew the young American Theodore Foley to the Passionists? What similarity was there between them? What grace led him on?

Brought up in a good family and a strong religious environment , Theodore Foley still felt “dangers and temptations” around him. No, he didn’t experience the social life that tempted Gabriel Possenti a century before. But he did experience the new mass media then sweeping the country. By 1922 movies, and to a lesser extent the radio, became powerful influences in people’s lives, and Hollywood’s heroes preached a new gospel of fun and success. Through the new media, the “Roaring Twenties” came to Springfield as it did to other prosperous parts of America when Theodore Foley was growing up. Did it bring the “the dangers and temptations” he feared?

Theodore Foley must have sensed the selfishness, the carelessness about others, the failure to appreciate suffering and weakness and sin in this new gospel. It promised life without the mystery of the Cross, but that was not real life at all. Only 14, he entered the Passionists.