Here’s Pope Leo latest reflection of the documents of the Second Vatican Council at his Wednesday audience yesterday, on the important subject of scripture and tradition:

“Dear brothers and sisters, good morning and welcome!

Continuing our reading of the Conciliar Constitution Dei Verbum on Divine Revelation, today we will reflect on the relationship between Sacred Scripture and Tradition. We can take two Gospel scenes as a backdrop. In the first, which takes place in the Upper Room, Jesus, in his great discourse-testament addressed to the disciples, affirms: “These things I have spoken to you, while I am still with you. But the Counsellor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you. … When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth” (Jn 14:25-26; 16:13).

The second scene takes us instead to the hills of Galilee. The risen Jesus shows himself to the disciples, who are surprised and doubtful, and he advises them: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations … teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Mt 28:19-20). In both of these scenes, the intimate connection between the words uttered by Christ and their dissemination throughout the centuries is evident.

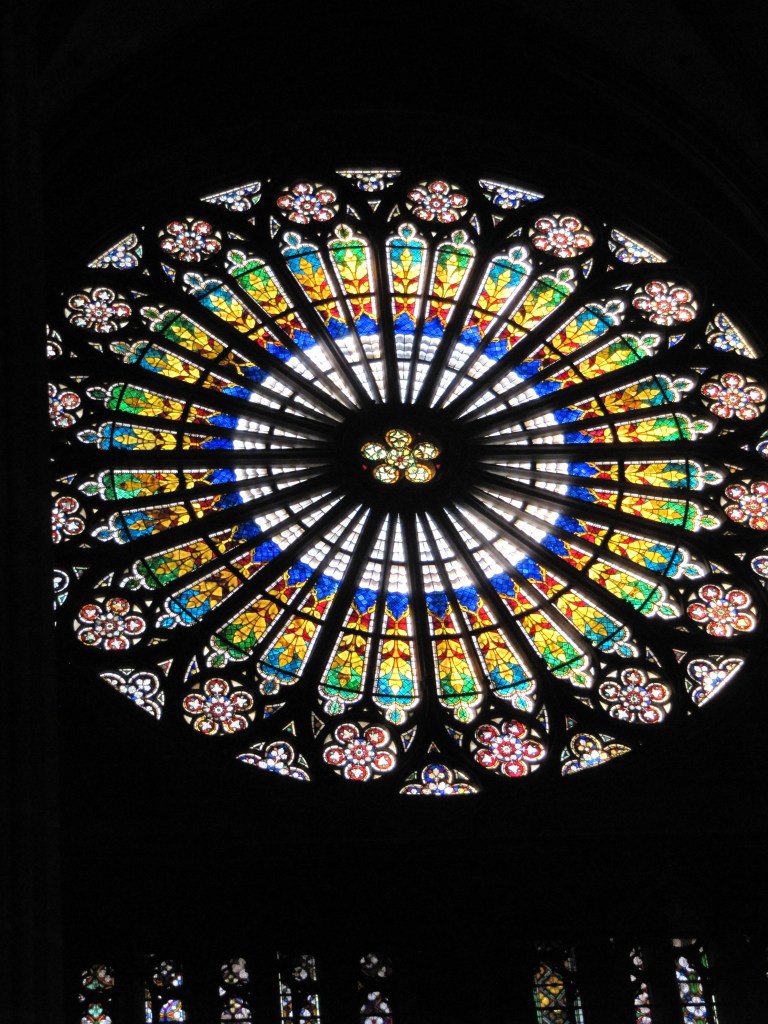

It is what the Second Vatican Council affirms, using an evocative image: “There exists a close connection and communication between sacred tradition and Sacred Scripture. For both of them, flowing from the same divine wellspring, in a certain way merge into a unity and tend toward the same end” (Dei Verbum, 9). Ecclesial Tradition branches out throughout history through the Church, which preserves, interprets and embodies the Word of God. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (cf. no. 113) refers, in this regard, to a motto of the Church Fathers: “Sacred Scripture is written principally in the Church’s heart rather than in documents and records”, that is, in the sacred text.

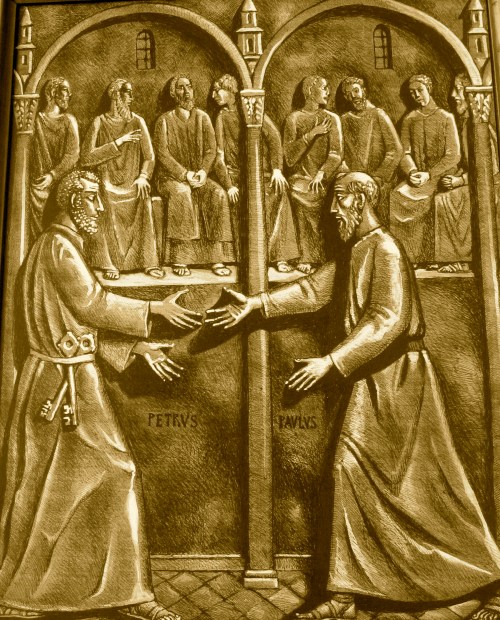

In the light of Christ’s words, quoted above, the Council affirms that “this tradition which comes from the Apostles develops in the Church with the help of the Holy Spirit” (Dei Verbum, 8). This occurs with full comprehension through “contemplation and study made by believers”, through “a penetrating understanding of the spiritual realities which they experience” and, above all, with the preaching of the successors of the apostles who have received “the sure gift of truth”. In short, “the Church, in her teaching, life and worship, perpetuates and hands on to all generations all that she herself is, all that she believes” (ibid.).

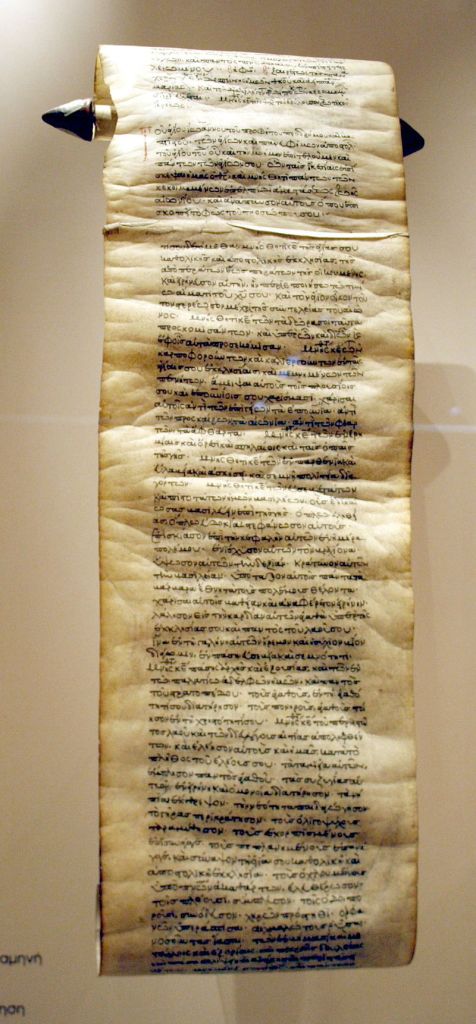

In this regard, the expression of Saint Gregory the Great is famous: “The Sacred Scriptures grow with the one who reads them”. [1] And Saint Augustine had already remarked that “there is only one word of God that unfolds through Scripture, and there is only one Word that sounds on the lips of many saints”. [2] The Word of God, then, is not fossilized, but rather it is a living and organic reality that develops and grows in Tradition. Thanks to the Holy Spirit, Tradition understands it in the richness of its truth and embodies it in the shifting coordinates of history.

In this regard, the proposal of the holy Doctor of the Church John Henry Newman in his work entitled The Development of Christian Doctrine is striking. He affirmed that Christianity, both as a communal experience and as a doctrine, is a dynamic reality, in the manner indicated by Jesus himself in the parables of the seed (cf. Mk 4:26-29): a living reality that develops thanks to an inner vital force. [3]

The apostle Paul repeatedly exhorts his disciple and collaborator Timothy: “O Timothy, guard what has been entrusted to you” (1 Tim 6:20; cf. 2 Tim 1:12-14). The Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum echoes this Pauline text when it says: “Sacred tradition and Sacred Scripture form one sacred deposit of the word of God, committed to the Church”, interpreted by the “living teaching office of the Church, whose authority is exercised in the name of Jesus Christ” (no. 10). “Deposit” is a term that, in its original meaning, is juridical in nature and imposes on the depositary the duty to preserve the content, which in this case is the faith, and to transmit it intact.

The “deposit” of the Word of God is still in the hands of the Church today, and all of us, in our various ecclesial ministries, must continue to preserve it in its integrity, as a lodestar for our journey through the complexity of history and existence.

In conclusion, dear friends, let us listen once more to Dei Verbum, which exalts the interweaving of Sacred Scripture and Tradition: it affirms that they “are so linked and joined together that they cannot stand independently, and together, each in their own way, under the action of the one Holy Spirit, they contribute effectively to the salvation of souls” (cf. no. 10).”

_______________________________

[1] Homiliae in Ezechielem I, VII, 8: PL 76, 843D.

[2] Enarrationes in Psalmos 103, IV, 1

[3] Cf. J.H. Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, Milan 2003, p. 104.