Dear brothers and sisters, good morning and welcome!

Continuing in our reflection on the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen gentium (LG), today we will look at the second chapter, dedicated to the People of God.

God, who created the world and humanity, and who wishes to save every man, carries out his work of salvation in history, choosing a real people and dwelling among them. For this reason, He calls Abraham and promises him descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and the sand on the seashore (cf. Gen 22:17-18). With Abraham’s children, after freeing them from slavery, God makes a covenant with them, accompanies them, cares for them, and gathers them together whenever they stray. Therefore, the identity of this people is given by God’s action and by faith in Him. They are called to become a light for other nations, like a beacon that will draw all peoples, the whole of humanity, to itself (cf. Is 2:1-5).

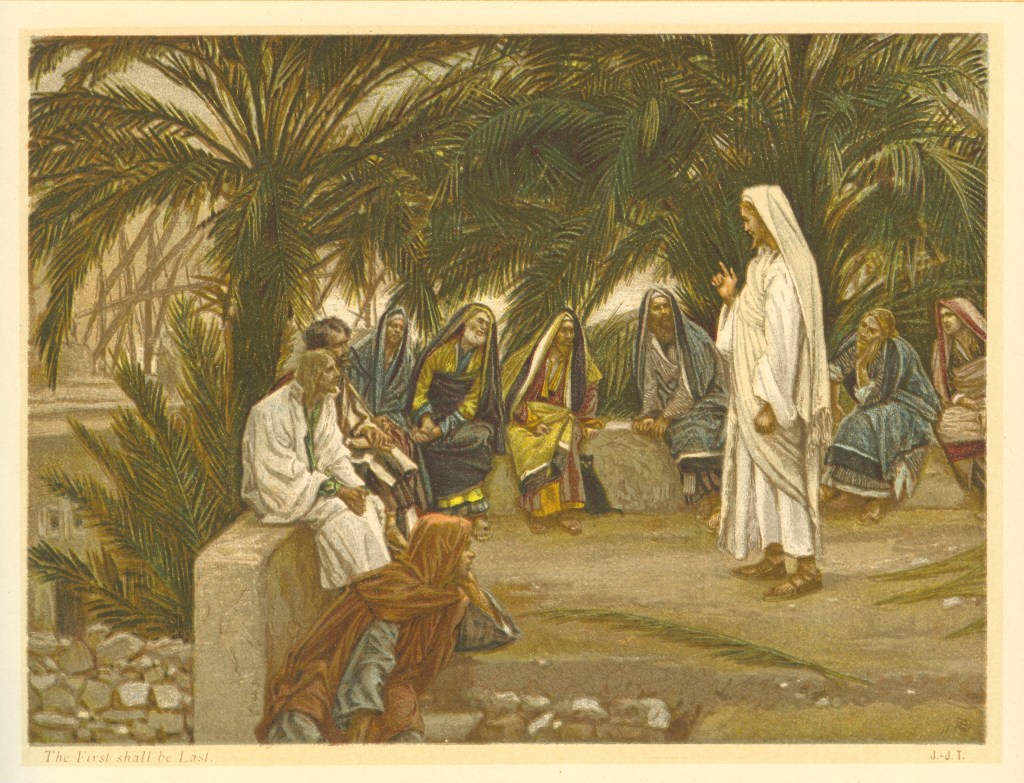

The Council affirms that “All these things, however, were done by way of preparation and as a figure of that new and perfect covenant, which was to be ratified in Christ, and of that fuller revelation which was to be given through the Word of God Himself made flesh” ( LG, 9). Indeed, it is Christ who, in giving His Body and His Blood, unites this people in Himself and in a definitive way. It is a people now made up of members of every nation; it is united by faith in Him, by adherence to Him, by living the same life as Him, animated by the Spirit of the Risen One. This is the Church: the people of God who draw their existence from the body of Christ [1] and who are themselves the body of Christ; [2] not a people like any other, but the People of God, called together by Him and made up of women and men from all the peoples of the earth. Its unifying principle is not a language, a culture, an ethnicity, but faith in Christ: the Church is therefore – according to a splendid expression of the Council – the assembly of “all those who in faith look upon Jesus” ( LG, 9).

It is a messianic people, precisely because it has Christ, the Messiah, as its head. Those who belong to it do not pride themselves on merits or titles, but only on the gift of being, in Christ and through Him, daughters and sons of God. Above any task or function, therefore, what really matters in the Church is to be grafted onto Christ, to be children of God by grace. This is also the only honorary title we should seek as Christians. We are in the Church in order to receive life from the Father unceasingly and to live as His children and brothers and sisters among ourselves. Consequently, the law that animates relationships in the Church is love, as we receive and experience it in Jesus; and her goal is the Kingdom of God, towards which she walks together with all humanity.

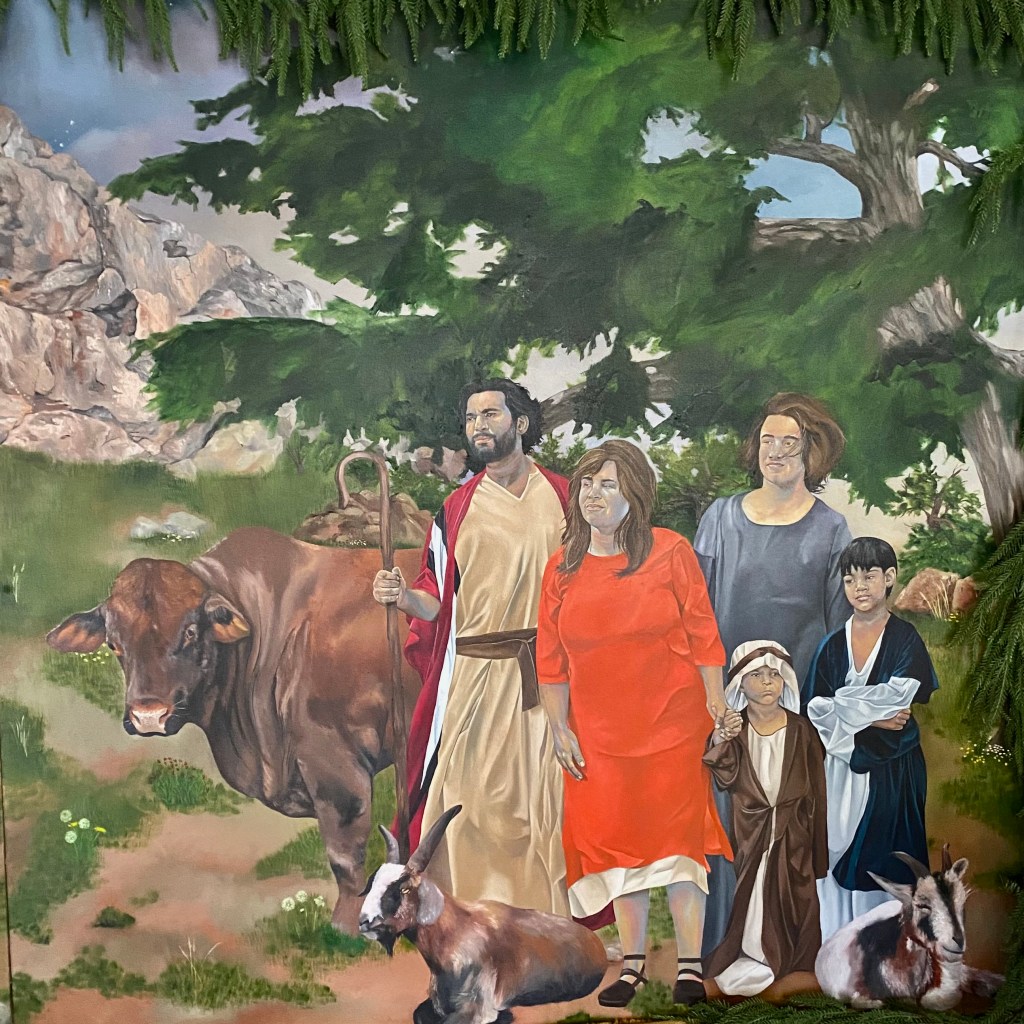

Unified in Christ, Lord and Saviour of every man and woman, the Church can never turn inwards on herself, but is open to everyone and is for everyone. If believers in Christ belong to it, the Council reminds us that “All men are called to belong to the new people of God. Wherefore this people, remaining one and unique, must extend to the whole world and to all ages, so that the intention of God’s will may be fulfilled, who in the beginning created human nature as one and wants to gather together his children who were scattered” (LG, 13). Even those who have not yet received the Gospel are therefore, in some way, oriented towards the people of God, and the Church, cooperating in Christ’s mission, is called upon to spread the Gospel everywhere and to everyone (cf. LG 17), so that every person may enter into contact with Christ. This means that in the Church there is, and there must be, a place for everyone, and that every Christian is called to proclaim the Gospel and bear witness in every environment in which he or she lives and works. Thus, this people shows its catholicity, welcoming the wealth and resources of different cultures and, at the same time, offering them the newness of the Gospel to purify them and to raise them up (cf. LG, 13).

In this regard, the Church is one but includes everyone. A great theologian described it thus: “The unique Ark of Salvation must welcome all human diversity into its vast nave. The only banquet hall, the food it distributes is drawn from all of creation. The seamless garment of Christ, it is also – and it is the same thing – the garment of Joseph, with its many colours”. [3]

It is a great sign of hope – especially in our times, traversed by so many conflicts and wars – to know that the Church is a people in which women and men of different nationalities, languages and cultures live together in faith: it is a sign placed in the very heart of humanity, a reminder and prophecy of that unity and peace to which God the Father calls all his children.

______________________________________________________

[1] Cf. J. Ratzinger, The New People of God, Brescia 1992, 97.

[2] Cf. Y. M.-J. Congar, A Messianic People, Brescia 1976, 75.

[3] Cf. H. de Lubac, Catholicism: A study of dogma in relation to the corporate destiny of mankind (Catholicisme: Les aspects sociaux du dogme).Ca