“Call no one on earth your father; you have but one Father in heaven. The greatest among you must be your servant. Whoever exalts himself will be humbled; but whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

Last week’s lenten readings were centered on prayer, this week’s readings, from Matthew and Luke, are about mercy. They wrote with a particular audience in mind. Both evangelists describe who Jesus is and what he taught, but each does it with an eye to his own time and place.

Matthew’s gospel, for example, was written for Jewish Christians who were living uneasily among their fellow Jews, possibly in Syria or Palestine, after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

The synagogues Matthew describes in today’s gospel are the synagogues of his time rather than the Galilean synagogues of Jesus’ day. They’re now in the hands of Jewish leaders trying to salvage Judaism after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

The current teachers “on the chair of Moses” are honored in Jewish society and on the streets, because they’re keeping Judaism alive. Jews are living together, praying in their synagogues and keeping their traditions in a new way, replacing the former discipline of the temple in Jerusalem.

Matthew’s gospel indicates the followers of Jesus are unwelcome, and so must be loyal to their teacher, even if he’s not recognized. He’s not a synagogue leader. He called himself a servant of all. He doesn’t have power in a synagogue; he has servant power.

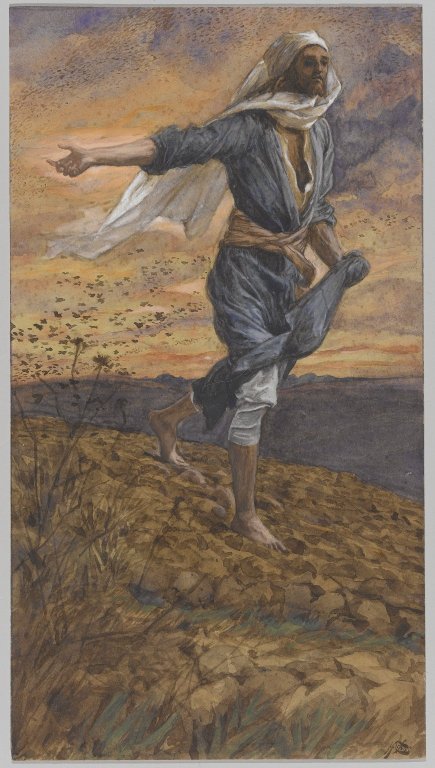

In this week of stories about mercy Matthew’s gospel is hard on the Jewish society of his day, while Luke introduces Jesus’ strong teaching on mercy: .“Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. Stop judging and you will not be judged. Stop condemning and you will not be condemned. Forgive and you will be forgiven. Give and gifts will be given to you. “

Luke’s parable of the Prodigal Son, which comes at the end of this week, is the story of a Father who loves his two sons. Can it be applied to the situation Matthew describes in our readings this week?

We’re living today in a highly partisan society. Can it also be applied to our situation now, when mercy can be forgotten in our war of words and actions?

Lord,

lead me away from temptations of self-importance,

as if my ideas, my vision, my convenience matter most.

You came to serve and not to be served.

Show me how to wish for what’s best for others

and save me from being a know-it-all.

Show me my faults,

and then take them away.