Yesterday I preached the homily at the Mass for Christian Burial for Father Quentin Amrhein, a Passionist priest who died at Queens Hospital, New York City, on July 31st and was buried at St. Paul’s Monastery, Pittsburgh, Pa., August 7, 2014. He was a member of the community at Immaculate Conception Monastery, Jamaica, New York, at the time of his death.

“Each of us is a witness to the gospel; we’re living gospels, however imperfect we may seem. What gospel did we see in Quentin?

We’ve been reading the parables of Jesus recently at Mass; the parable of the sower; the parable of the treasure hidden in the field, the mustard seed, the parable of the net cast into the sea. I wonder if Quentin’s life might tell what some of those parables mean. Parables need to be explained and sometimes the best explanation comes, not from books, but from people who are living gospels.

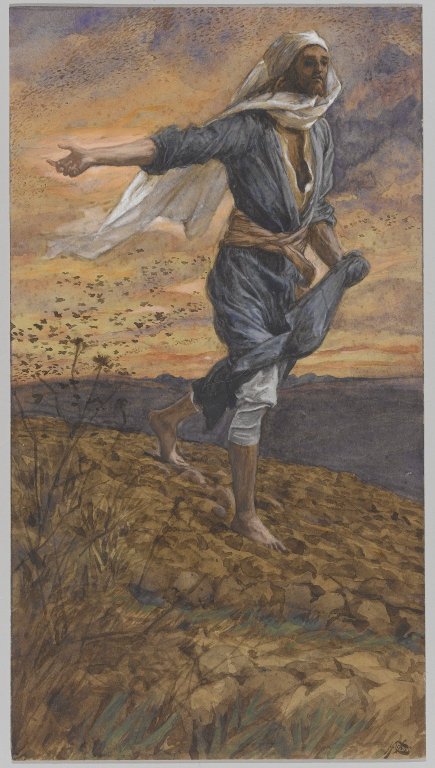

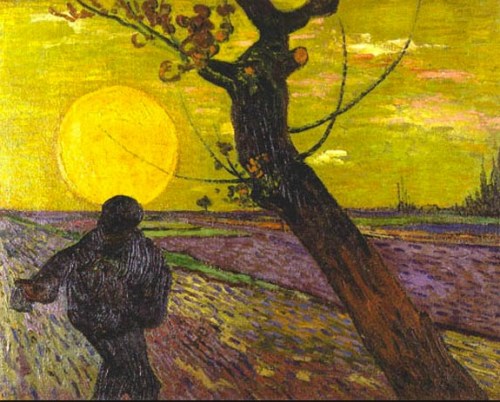

God the Sower is one of Jesus’ most important parables. He’s the sower who sows seed in the field of humanity. He never stops sowing; from the first moment of creation, from the first moment of our lives, God is at work sowing good seed. Sometimes the growth is quick and obvious, sometimes it isn’t. Sometimes the growth is delayed, but all our life long, God is the sower sowing good seed. And he doesn’t stop.

In a poem called “Putting in the Seed” Robert Frost describes what he calls “a farmer’s love affair with the earth.” It’s spring and getting dark, but the farmer keeps working his field. Someone from the house goes to fetch him home. Supper’s on the table, yet he’s a

“ Slave to a springtime passion for the earth.

How Love burns through the Putting in the Seed

On through the watching for that early birth

When, just as the soil tarnishes with weed,

The sturdy seedling with arched body comes

Shouldering its way and shedding the earth crumbs.”

Isn’t that a good image of God: a Sower, passionately in love with our world, casting saving grace on it in season and out, and watching it grow?

God blessed Father Quentin. He came from a good Pittsburgh family with strong Passionist roots. His grand uncle, Father Joseph Amrhein, served the Passionist community in Rome and in the United States. His uncle, Father Leonard Amrhein, was a missionary in China and then the Philippines. His younger brother, Raphael, was a Passionist priest, and his sister, Mary, was a Passionist Nun who died a missionary in Japan. Quentin was always proud and grateful for his family.

He was blessed by God with a keen mind and an exceptional memory. Those who knew him marveled at the way he recalled in detail things that took place 20, 30, 40 years ago. I remember him telling me the line-up of the 1944 Pittsburgh Pirates.

But much of Quentin’s life was clouded by sickness of one kind or another, which prevented him from doing many of the ministries a Passionist priest does. He loved preaching, yet for many years he wasn’t able to preach. He loved to study, and yet sickness kept him from doing that as well.

What we noticed in him in recent years, though, was not the sickness but the way he persevered through the suffering and disappointments that sickness brings. He wasn’t beaten by it; he fought the good fight. He was an exceptional fighter. At our wake service for him in Jamaica, a doctor and members of the medical community who cared for him through recent life-threatening crises spoke admiringly of Quentin’s determination to live. He came back again and again from death’s door.

How did he do it? Was it simply him? Was it his strong personality, good constitution, or German determination? We usually explain things like this in purely human terms.

Yet, if the gospel is at work in us, was God at work in him? Do we see in him God the Sower tending the life of his seed and seeing it grow?

Last week before he died, Father Quentin celebrated and preached at the community Mass at our Jamaica monastery. He hadn’t done that in years. The thirty of us who were there that day will remember that Mass for a long time, I think. It was a beautiful Mass: we were watching a promise come true. A resurrection, a Lazarus come to life.

It was like watching the birth of a seed, as Frost describes it in his poem:

“The sturdy seedling with arched body comes

Shouldering its way and shedding the earth crumbs.”

I said to Father Quentin after that Mass, “ I hope you are going to do that again.” “Yes, I am,” he said, “ the vicar has me down for celebrating Mass for the Feast of the Transfiguration.” Then he went on to tell me with his usual enthusiasm, how the Lord shares his glory with us as he did Moses and Elijah and the apostles. But first, we have to follow him in suffering, as he told his apostles when he predicted his passion to them.

Last Wednesday was the Feast of the Transfiguration, but Quentin was not going to preach that day. God was going to bring him up the mountain to share his glory with him.

We’re living gospels and Quentin was a gospel to us. He’s a reminder that God the Sower is always at work in the world, in a world where we think that people with long term disabilities are going nowhere, in a world where we think that life ends with youth, in a world where we think that suffering has no meaning, where we think there’s no resurrection and God has given up on us.

The Gospel of Quentin. I know he would be the last to call it his gospel, because he saw it as the gospel of Jesus, whom he served and love and prayed to and relied on all his life. Today as we commend him to God we read from the Gospel of John a passage he himself chose for this Mass.

“The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified. Amen, amen, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat; but if it dies, it produces much fruit. Whoever loves his life loses it, and whoever hates his life in this world will preserve it for eternal life. Whoever serves me must follow me, and where I am, there also will my servant be. The Father will honor whoever serves me.”

The seed has fallen to the ground, but it will bear much fruit.”

(Vincent Van Gogh painted the Sower (above) many times and found the subject filled with spiritual significance. He once said “one begins to see more clearly that life is a kind of sowing time, and the harvest is not here.”).