Neil O’Donnell, a small farmer from Donegal, Ireland, where the crops had failed for years, came to the United States in 1882 and landed at Castle Garden at the Battery in New York City along with countless others looking for work and a home.

Castle Garden 1880s

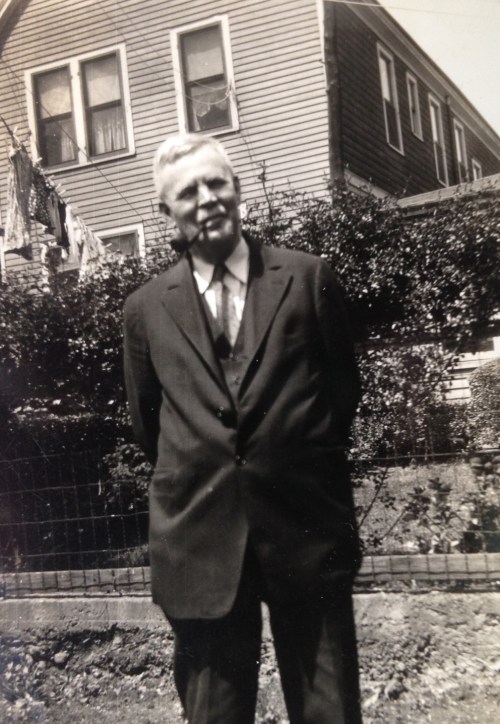

Among my boyhood memories, I remember sitting in the summer on the front porch with the old man in the picture above with a pipe in his mouth. “Allo Bye,” he would shout out to passers-by in a thick Irish brogue. His sight was failing, but once the passer-by was known a lively conversation began about families, friends, the weather and everything else going on in close-knit Bayonne.

Neil died in 1942. I remember kneeling with my family, friends and neighbors outside his room next to the kitchen saying the Rosary as he was dying. I was at his big funeral at St. Mary’s church. Irish funerals were always big then, but this one was special I felt. A patriarch had died.

Neil didn’t look far for a job or a home when he got off the boat at Castle Garden. From the Staten Island Ferry, near the docks at St. George, you can still see today oil tanks at Constable Hook on the western shore of the harbor in Bayonne, NJ. In Neil’s day this was The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, but for him then it was “Hughie Sharkey’s oil works” where he got the job he held all his working life. Hughie Sharkey was the guy who got Neil and Irishmen like him a job.

Neil married Sarah Givens, also from Donegal. They had six kids, four boys and two girls. Sarah died after the last was born and Neil brought his sister Mary out from Ireland to take care of the kids, but unfortunately she died shortly afterwards too.

“We made our way up in the world,” my mother often said. From a small house on 19th Street in Bayonne, they made their way to a two decker house on the Boulevard about a half-mile away. The first three kids had a minimal education, but the last three got more. My mother was the first to graduate from high school; the last two boys were sent to the Jesuit St. Peter’s High School in Jersey City. One became a priest, the other a New Jersey State Trooper.

A close immigrant family in a solidly Catholic neighborhood, the O’Donnells took care of each other and watched out for their neighbors too. Regularly, they brought others out from Ireland and helped them find jobs and homes of their own. They remembered where they came from.

With all our talk about immigrants these days, I think of Neil, the small farmer from Donegal where crops were failing, who found in America a job and a place to raise a family. His hours were long and his work was tough. The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey fiercely resisted workers’ demands for unionization and better working conditions in his day; in fact, it hired strike breakers to squash workers’ protests. My mother remembered when she was a girl a terrible day some workers were shot and killed near their home. But Neil and his boys working at the Hook never missed a day.

They never missed church either. With simple unquestioning faith they prayed at St. Mary’s church on 14th. St. They reverenced the priests and sisters there; they were especially fond of the Passionists priests who preached and served the parishes of Hudson County from their monastery in nearby Union City. Faith was never a small part of their lives.

Neil could scarcely read when he came to this country, my mother said, and one thing he wanted was to read the Bayonne Times like everyone else. She taught him how to read. I remember the old man, newspaper in hand, bent on getting the news of the day, like everyone else.

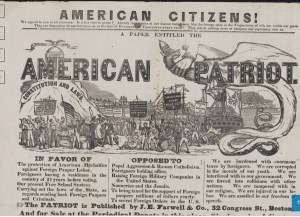

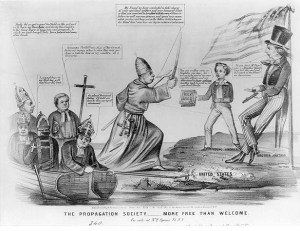

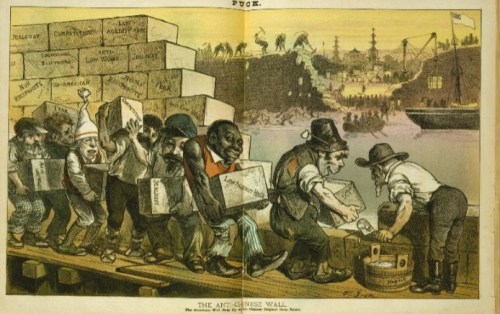

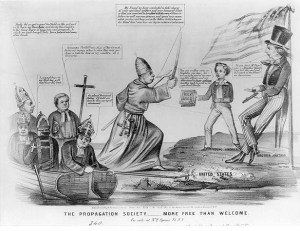

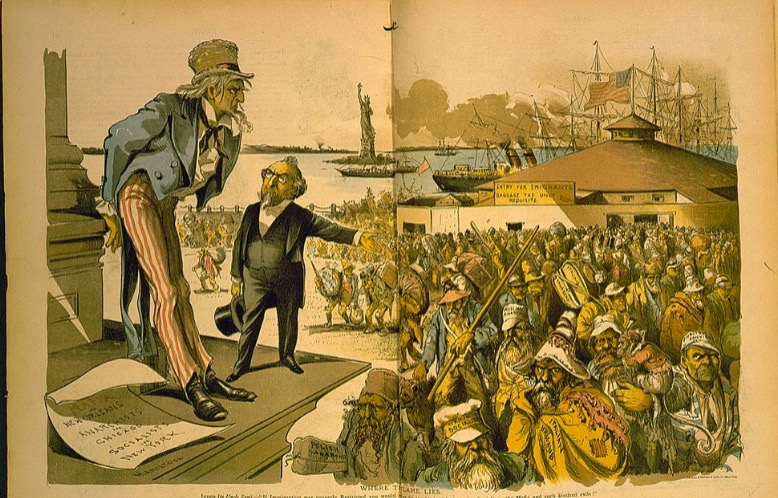

Not everyone in America appreciated Neil and immigrants like him, however. Nativist sentiments affected much of the country then as large numbers of foreigners, especially Irish Catholics, came to our shores. To some they brought poverty, disease and crime to America. Laws were proposed advocating literacy requirements and denial of voting rights to them. Catholics were denied jobs and access to political offices. Neil would never have made it here if the Know-Nothings and nativists had their way.

We celebrate our country’s generosity and openness to the world; but we can’t forget the ugly side of our history. You can see it here in some Nativist broadsheets and cartoons from the time, voices Neil must have heard. They’re still with us today in more subtler forms.

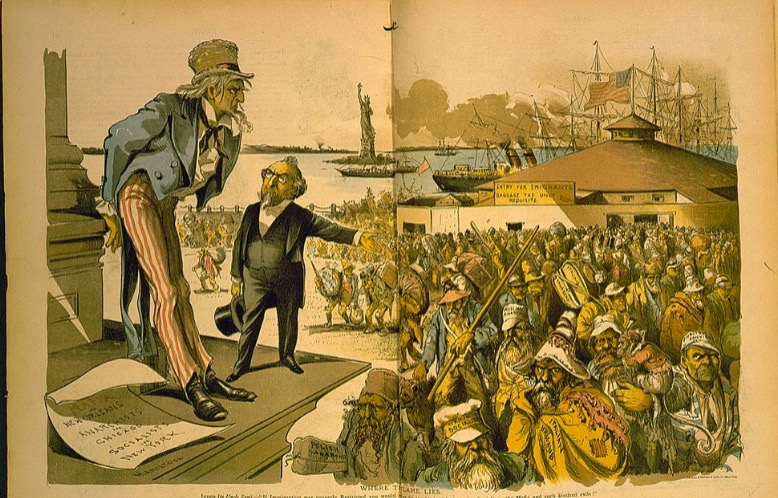

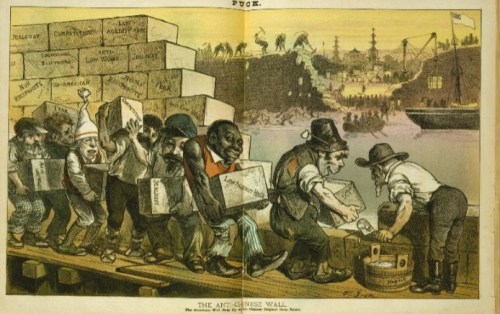

Among the anti-immigrant material I found, I came upon one that made me stop and wonder some more. In the 1880s the United States was pushing China for access to her markets. We wanted free ports and free trade with that land and demanded she take down her walls.

At the same time, Chinese laborers were entering our country, chiefly the west coast, to work on the railroads. They were cheap labor, competing with the Irish, the Italians and other immigrants for jobs. In 1882 Congress prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the country.

A Punch cartoon from that time saw the irony of the situation. We demand walls be pulled down and put up walls ourselves. Look carefully, though, at who brings the bricks for our wall. Immigrants like the Irish and others who came here, often not welcomed themselves.

I wonder what Neil would say about this? I wonder what his descendants are saying about immigration today? We who come from an immigrant church.