We celebrate the Feast of the Assumption of Mary into heaven August 15th. It’s the most important feast of Mary in the church’s calendar. Where did it come from?

There’s no account of Mary’s death or assumption into heaven in scripture. An account in the apocryphal body of literature called the Transitus Mariae, popular in the Christian churches of the east from the 5th century, describes the return of the apostles to Jerusalem for Mary’s burial and their discovery that her body was taken up to heaven. The writings attest to an early interest in the death of Mary in some parts of the early church.

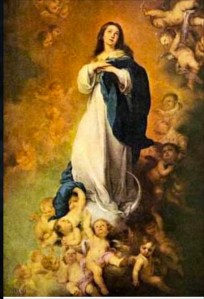

The first liturgical celebrations of Mary’s death and assumption to heaven took place in Jerusalem at her tomb (above) on the Mount of Olives about the 5th century. The Roman Catholic Church draws her present belief from this early tradition and her conviction that Mary is “wholly united with her son in the work of salvation.” For scriptural support, the church looks to sources like Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians–the second reading at Mass for August 15th – to understand this mystery.

Paul wrote that letter about the year 56 AD to Corinthian Christians who had questions about the resurrection of Jesus. Their precise difficulty seems to be that they saw only the soul surviving death and not the body, a common conception of the Greek mindset of the day. That belief brought a low appreciation of the body and the place of creation itself in the mystery of redemption. The created world wasn’t worth much and was passing away, so let it go.

Paul countered that opinion with the belief he received, a belief from the beginning: “For I handed on to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures; that he was buried; that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures; that he appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at once, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep” (1 Corinthians 15: 3-6).

Jesus was raised bodily from the dead, Paul affirms, and we will rise bodily too. Jesus is “the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.” Mary’s bodily assumption follows the bodily resurrection of Jesus. Because of her unique role in the mystery of redemption she is among the “first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.” Her assumption is part of the mystery of the resurrection; it’s an affirmation we will follow Jesus who rose body and soul.

In her prayer, the Magnificat – the gospel read on the Feast of the Assumption – Mary accepts her mission from God to share in the mission of her Son, the Word made flesh, who came to redeem the world.

The church gradually understood the mystery of Mary’s Assumption over time. A rising Gnosticism in the 3rd and 4th centuries certainly promoted appreciation of this mystery. Gnosticism promised escape from the limits of bodily life through a higher knowledge. As a result, human life and creation itself didn’t matter.

Mary’s Assumption claims they do.

The Roman Catholic Church formally defined the dogma of the Assumption on November 1, 1959, on the Feast of All Saints, but the belief was firmly held for centuries before:

“…the Immaculate Virgin, preserved free from all stain of original sin, when the course of her earthly life was finished, was taken up body and soul into heavenly glory, and exalted by the Lord as Queen over all things, so that she might be the more fully conformed to her Son, the Lord of lords and conqueror of sin and death.” The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin is a singular participation in her Son’s Resurrection and an anticipation of the resurrection of other Christians: ‘In giving birth you kept your virginity; in your Dormition you did not leave the world, O Mother of God, but were joined to the source of Life. You conceived the living God and, by your prayers, will deliver our souls from death'” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 966).

Mary’s Assumption was defined in a century when human life and the planet itself were threatened. World War I ended in 1918 after four years when millions perished. World War II, ending in 1945, left the real possibility that war and nuclear weapons could bring about the destruction of the human race. The Holocaust seemed to prove the capability of human evil.

Threats to human life continue and creation itself is increasingly endangered by climate change and consequent poverty. August 15, the date for the celebration of this feast from earliest times, is the time of harvest for most of the Western Hemisphere. Our belief in the resurrection of the body sees creation itself promised a share in this mystery. The readings and prayers of the feast describe Mary in heaven as the woman clothed with the sun, the moon and the stars beneath her feet. (Revelation 11)

The Feast of Mary’s Assumption is the oldest and most important of Mary’s feasts in our church calendar.